/17

More Projects

-

Arenakvarteren - With C.F. Møller

-

NOVO

-

Morris Law Drottninggatan

-

The Tailor

-

Spanjoletten

-

Krog Agrikultur

-

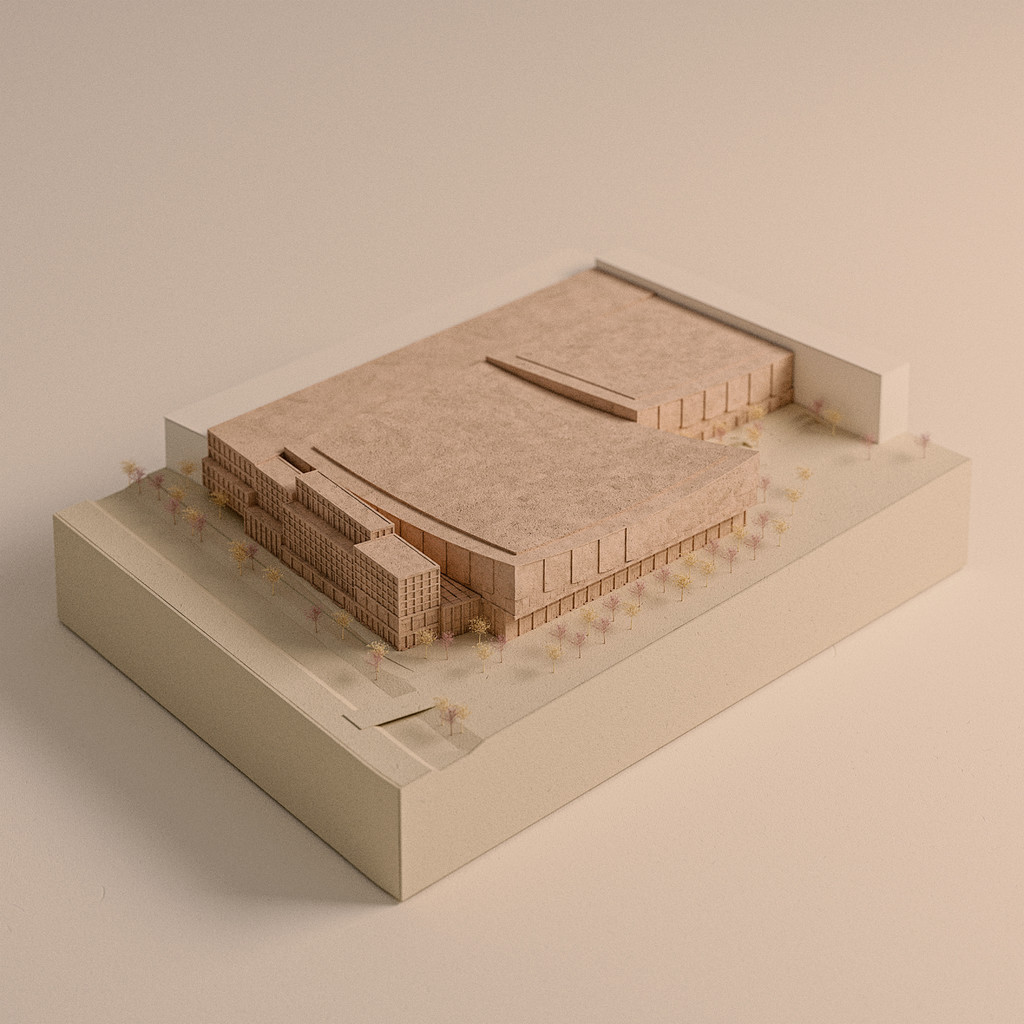

Gothenburg Art Museum - With Herzog & de Meuron

-

Furillen

-

Lundbypark

-

Hydri

-

Ullevi offices and tennis

-

Fryshuset

-

Polestar Ålesund

-

Villa Hamnfyren

-

Kallebäck

-

Villa Lyckan

-

Surte LSS

-

Merkurhuset

-

Draken Restaurant

-

Gurras

-

Villa CO

-

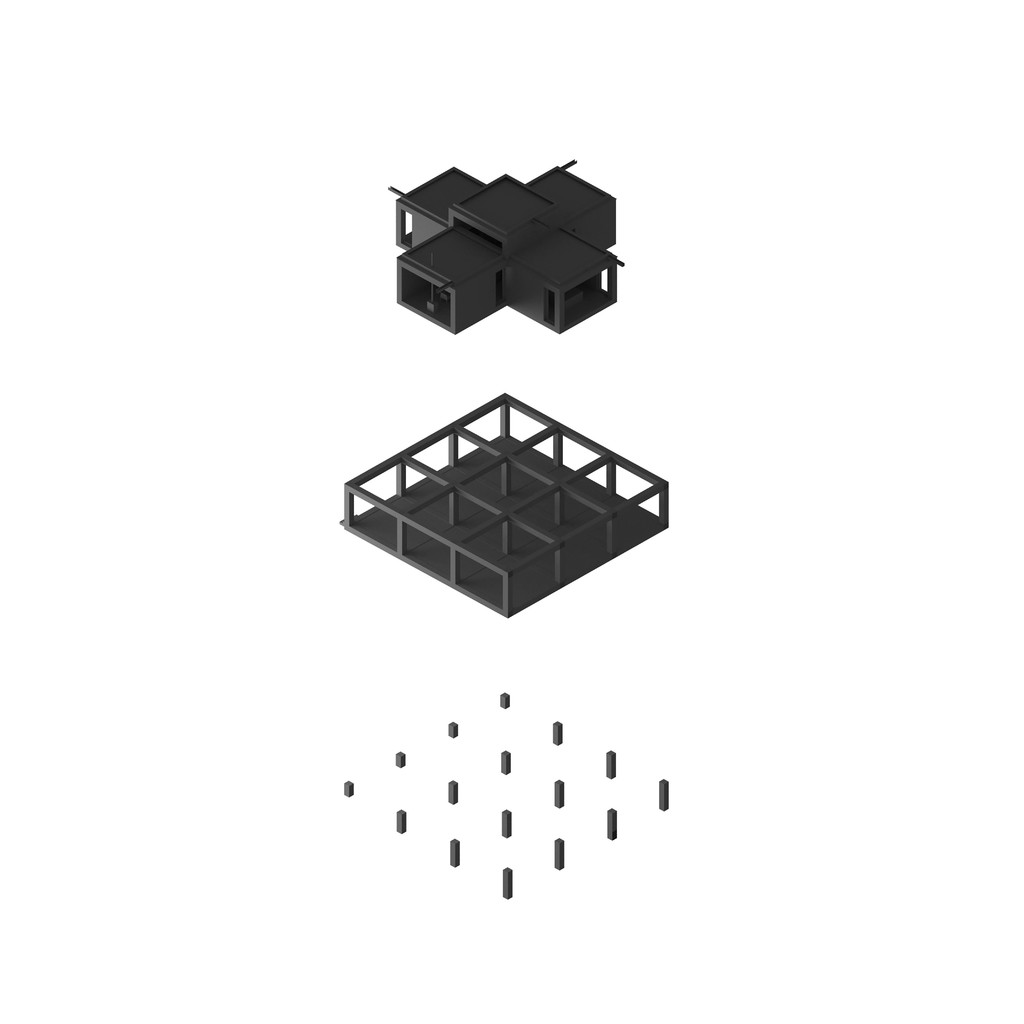

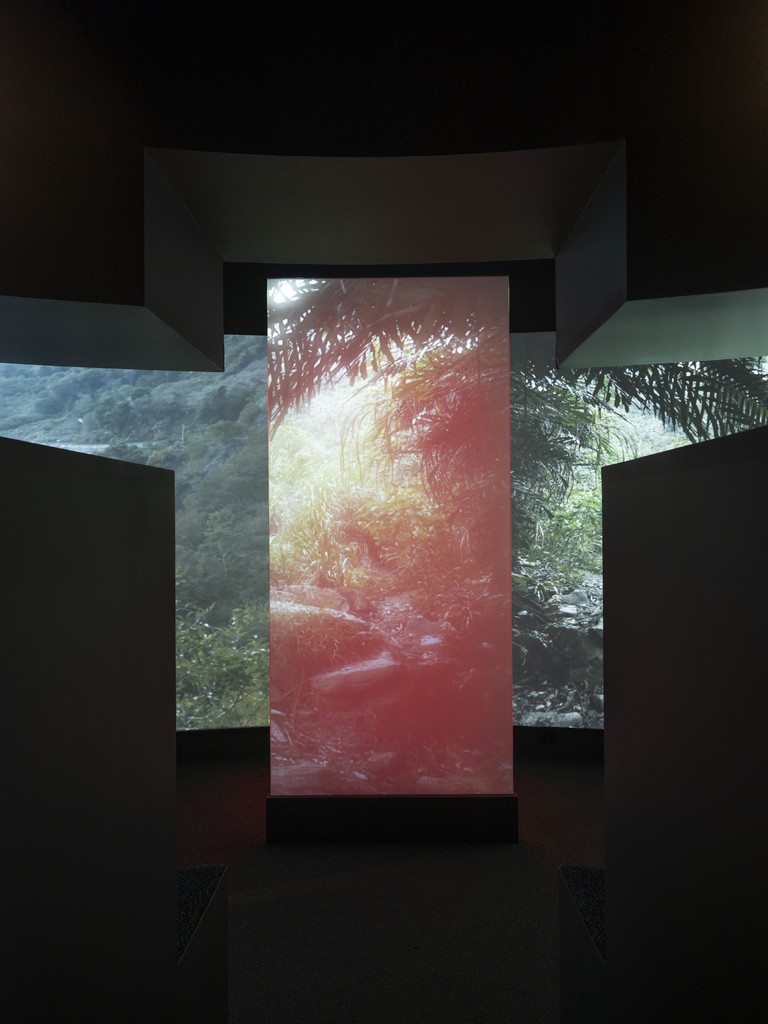

Flexible Exhibition space / We Are Seediq at the Museum of Etnography

-

Draken Hotel

-

Polestar HQ

-

Human

-

Forsman & Bodenfors

-

Chang

-

Axel Arigato

-

Polestar Landvetter

-

Villa Ashjari

-

Björlanda

-

Trädgården

-

Folkets Hus

-

Polestar Århus

-

Brunnsparken

-

Villa Timmerman - With Josefine Wikholm

-

Capella

-

Späckhuggaren

-

Kärdla

-

Stampgatan

-

Villa Hovås

-

Villa R

-

Villa Amiri

-

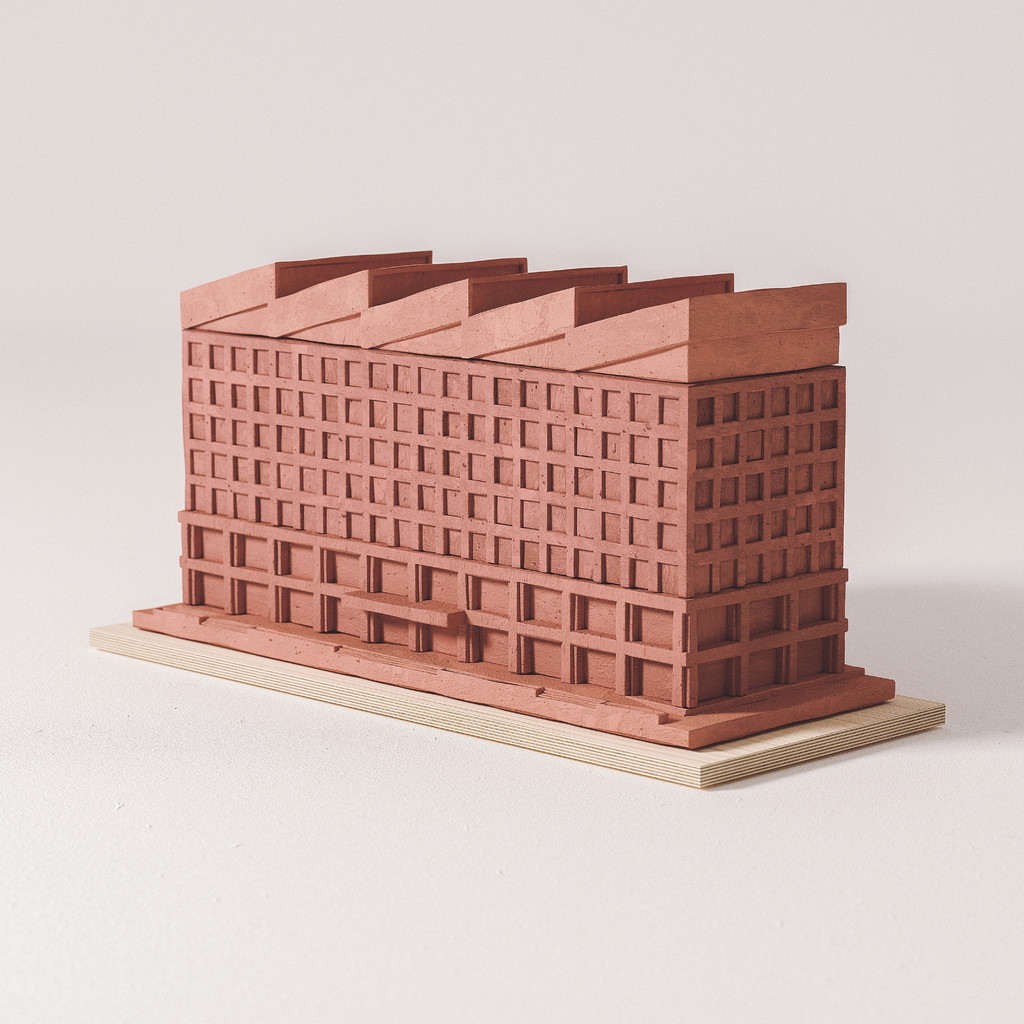

Qvillestaden

-

Boulebar Liljeholmen

-

Apartment C/O

-

Gibraltar Guesthouse

-

Granholmen

-

Kokillen

-

Morris Law Gothenburg

-

Koka